Lord Here We Are

Lyric:

Lord here we are, here we are, here we are

Listen, listen, ooh, ooh,

Ears are made for listening

Shower your blessings, you who feels our pain

Shower your blessings, let love fall like rain,

Shower your love, my Shariqallah!

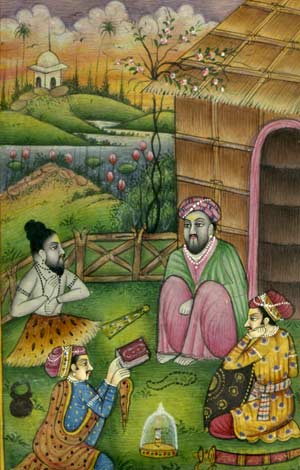

North India Moghul period miniature depicting a yogi–on the left–and the Sufi on the right sitting before his hut.

Comment:

This is based on a Quwwali song, a form of Sufi devotional music popular in India and Pakistan. As a distinct musical style, Quwwali developed in the 13thcentury, about the time the Bhakti movement was getting established in Northern India. The two share so many qualities it is hard to imagine they didn’t influence each other. Both use chant-like refrains, both employ a troupe of singers with one or two leaders, both accompany the vocals with harmonium and tabla or dolak and both are intense devotional music. Whether a wazifa (a Sufi name for a chant), or a bhakti kirtan, the singer opens the heart and calls on the Divine.

Lord, Here We Are is a translation from the Urdu of a portion of a traditional Quwwali song. It captures a spiritual sentiment common in both Bhakti and Sufi traditions: when a devotee’s longing is sufficiently pure and sustained, God will respond. There are a number of Sufi poems and spiritual practices of a similar type aimed at drawing God’s attention to the soul’s longing.

The following quatrain, by the great fourteenth-century Persian Sufi poet, Hafiz, from his song Bia Ta Gol captures this same sentiment.

Oh East Wind, take this dust of mine,

Throw it out, to the One Divine

So the King of Grace and Beauty may,

Turn His face, and throw a glance our way.

Shiva Hara

Lyric:

The Mahamrtiyunjaya Mantra

Om Tryamabakam Yajamahe Sugundhim Pushtivardhanam

Urvarukamiva Bandhanaan

Mrityormoksheeya Maa-amritaat.

Translation:

I bow to the all-seeing Lord of the Universe

Who is filled with the sweetest fragrance,

Who nourishes all human beings.

May He free me from the bondage of samsara and death

Just as the ripe cucumber falls from the branch.

May I be fixed in immortality.

Translated by Ma Yogashakti

Shiva Hara

Shiva Hara Shiva Hara Shiva Hara Shiva Hara

Samba Sada Shiva Hara Hara Hara Hara

Translation:

Praise to the Auspicious One, destroyer of ignorance, eternally full of happiness! Praise!

Comment:

This chant opens with a conch, a sacred Indian instrument used in temple worship believed to capture the sound of the cosmic Om – the universal sound. The stringed instrument with the remarkable twang is a tambura, a classical Indian instrument played here by David Ballman. The tambura creates the drone sound which underlies Indian classical music. Sharing the foundation is a chorus of Oms. The mantra is a revered one honoring Shiva. There is a story behind this chant which is worth telling.

My first trip to India was in the winter-spring of 1974. I was young, idealistic, and enthralled with yogic mysticism. I spent the bulk of my time in an ashram near Gondia, Maharashtra State, a west central Indian city of 70,000 on the main Bombay to Calcutta (Mumbai to Kolkata) rail line, not far from Nagpur. I was studying yoga and Indian philosophy with my future guru, Ma Yogashakti. We affectionately called her Mataji (Revered Mother).

After several weeks at the ashram, I began wondering if I should ask Mataji to initiate me. I was uncertain. Finding a real guru is an important step on the path. I said nothing, although I was thinking about it a lot. One morning, I was silently pondering this very question while sitting in the ashram’s Satsang Hall with Mataji and several of her students. Suddenly, she looked at me and said out of the blue, “I will initiate you.” Well, that settled it! Any guru who can read my mind wins my respect. My upcoming initiation marks a turning point in my spiritual development. It has sustained me since.

This was in the beginning of February 1974. She set the date for my initiation on the upcoming holy celebration of Shiva Ratri, or the Night of Shiva. In the Hindu Lunar Calendar, this occurs on the night of the dark moon of February. Shiva is a powerful primordial manifestation of the eternal Spirit and is as old as India. Mythologically speaking, this is the night that Shiva, the Lord of Yoga and his consort the Goddess Shakti marry. Their lovemaking births the universe.

I received my mantra initiation (mantra diksha) from Mataji the afternoon of the night of Shiva Ratrai. As night began to fall on this holy day, two brothers who lived in the area came to the ashram to celebrate Shiva Ratrai. They went to Satsang Hall on the grounds of the ashram and began the chant featured here on the CD – Shiva Hara. They sang with enormous passion, clapping, dancing and carrying on for hours. I remember sitting there, astonished. Eventually, I went to bed. Periodically, I woke up during the night and could hear their voices wafting through the night air. They didn’t stop until the sun came up.

When I returned home to South Florida, teachers at Mataji’s yoga ashram in Deerfield Beach knew that I was a musician and asked me to lead a chanting group there. I obliged. We called the program Satsang, Sanskrit for a spiritual gathering. For the next several years I led chanting there every Sunday night. I first performed Shiva Hara at these gatherings, and have continued to do so in chanting and kirtan groups ever since.

This is a powerful chant. One benefit that appears to come from it is that it can clear away toxic emotions for those who sing it with devotion. Such an effect aligns with the sacred name, Hara, which means the one who destroys all, including that which is dysfunctional and coming apart in the universe.

This is a powerful chant. One benefit that appears to come from it is that it can clear away toxic emotions for those who sing it with devotion. Such an effect aligns with the sacred name, Hara, which means the one who destroys all, including that which is dysfunctional and coming apart in the universe.

In Hindu cosmology, Shiva is formless Spirit, existing in eternity, prior to the manifestation of time, space, and matter. Over the Indian millennia, however, Shiva has assumed different mythic forms.

One embodiment is Nataraja, the Lord of the Dance, whose rhythmic movements bring the universe to life. Nataraja holds a drum which beats out nature’s pulse. Gary’s fiery tabla solo on this chant is fitting. The violin is a western instrument which has been embraced by Indians, and is often used in their traditional music. Since it is fretless, it can play the unusual intervals and slide tones typical of Indian classical music. Dalyce’s solo, which swirls and dances and spins invokes the dancing, writhing form of the glorious Nataraja.

One embodiment is Nataraja, the Lord of the Dance, whose rhythmic movements bring the universe to life. Nataraja holds a drum which beats out nature’s pulse. Gary’s fiery tabla solo on this chant is fitting. The violin is a western instrument which has been embraced by Indians, and is often used in their traditional music. Since it is fretless, it can play the unusual intervals and slide tones typical of Indian classical music. Dalyce’s solo, which swirls and dances and spins invokes the dancing, writhing form of the glorious Nataraja.

Salutations to the Lord of the Dance!

Om Shakti Ma

Lyric:

Om Ma Om Ma Om Ma Om Shakti Ma

Om Ma, Om Shakti Ma Om Ma Om Shakti Ma

Om Ma Om Ma Om Ma Om Ma

Translation:

Praise the Universal Mother Power! Praise Om! (the cosmic sound)

Praise Om! (the cosmic sound)

Comment:

In Indian cosmology, the power which brings the universe into manifestation and which births the human soul is feminine, the Universal Goddess of Life. In her manifestation as creative power, she is known as Shakti. Ma means Mother and Om is the cosmic sound. The sacred view of the Shaktaites – those who worship this Diety, see her as a mother. Shakti is loving and compassionate to her universal creation, for that is verily her own body. We are her children, living out our existence in the ocean of her Being.

The reedy-sounding instrument on Om Shakti Ma which is featured on other chants on this Wild Moon Bhaktas CD is an accordion. That may seem like an odd instrument for this music, but it is actually appropriate. Both the harmonium – the standard instrumental accompaniment for Indian chanting – and the accordion make their sound by the same principle: a bellows blows wind across a free reed. The open reed style’s ancient origins is in the East. A mouth harmonica works on the same principle.

The harmonium was created in Western Europe in the 18th century. Within several decades it became the instrument of choice for foreign missionaries and American frontier folk because it was easy to transport, and it didn’t go out of tune like the piano. Upright harmoniums with their bellows pumped by foot action found their way into many pioneer homes and country churches. Christian missionaries brought the harmonium to India in the 19th century, where the local instrument makers adapted it to their own use. They removed the seated foot pumping action, cut off the entire base and moved the bellows to the back of the instrument so that people could sit on the floor in traditional Indian style and play.

Classical Indian music does not contain harmony, so one need not have a second hand to play harmonic chords or bass lines, as in western music. With the Indian harmonium, one hand pumps the bellows while the other hand plays out the melody on the keyboard. This makes the instrument easy to play because one needs only to direct a single finger along a keyboard to carry the melody.

Today, the harmonium is the instrumental accompaniment of choice for most Hindu, Sikh, and Sufi Quwwali devotional chanting groups. Not everyone is sold on the idea, however. Traditional Indian musical purists reject the harmonium as a western instrument, and prefer indigenous stringed instruments to accompany their bhajans and kirtan. Ironic isn’t it? Many western practitioners of kirtan see the harmonium as a traditional Indian instrument, when in fact, it is a western import.

An accordion player with a banjo player; 19th century Louisiana.

Compared to the harmonium, the accordion, a 19th century European creation, has the capacity for greater harmonic and chromatic arrangements because both hands make music. The left hand pumps the bellows and plays the bass and chord buttons while the right hand plays the keyboard. Due to this sonic expansion, the instrument makes a bigger sound than the harmonium.

I believe the Wild Moon Bhaktas are the first kirtan band in North America to use the accordion on a regular basis. Due to the instrument’s bellows, it is hard to sit on the floor and play. For that reason, for Wild Moon Bhaktas events, I sit in a chair.

The accordion has successfully reached North and South America and parts of Africa where it has been incorporated into indigenous music. But it has not yet made an impact in South Asia. What will happen when Indians embrace the accordion?

Narayana/Near Your Breastbone

Lyric:

Narayana Narayana Jaya Govinda Hare

Narayana Narayana Jaya Gopala Hare

Near your breastbone, near your breastbone

There is a flower

Drink the honey, drink the honey,

All around that flower.

Translation:

Narayana is the Divine emanation from which all beings come. Jaya means praise or victory. Govinda is the one who fulfills the promise of the scriptures, Gopala is a manifestation of the Avatar Vishnu, in his form as the youthful cowherd, Krishna, and Hare is a traditional invocation.

Here is one way to say it:

Praise to the Lord of All Creatures, the Redeemer and the Herder (of cows and souls). All hail!

Comment:

The English lyric is drawn from a poem by Kabir, India’s 15th century visionary and mystic. He is one of the most loved and respected figures of North India’s Bhakti movement. Little is known about his life. Born of a lower Hindu caste in the 15th century Moghul era, Kabir lived near Benares, the holy city of the Hindus. He was a weaver whose family had most likely recently converted to Islam. That likely explains what sparked the synthesis of Hindu and Persian Muslim influences which surface so confidently in Kabir’s writings. Writings and poems attributed to him reveal a lively-minded iconoclast, an eschewer of formal religion and a challenger of material complacency. He mocks religious pompousness while declaring that we should all surrender to God now when we can.

The English lyric is drawn from a poem by Kabir, India’s 15th century visionary and mystic. He is one of the most loved and respected figures of North India’s Bhakti movement. Little is known about his life. Born of a lower Hindu caste in the 15th century Moghul era, Kabir lived near Benares, the holy city of the Hindus. He was a weaver whose family had most likely recently converted to Islam. That likely explains what sparked the synthesis of Hindu and Persian Muslim influences which surface so confidently in Kabir’s writings. Writings and poems attributed to him reveal a lively-minded iconoclast, an eschewer of formal religion and a challenger of material complacency. He mocks religious pompousness while declaring that we should all surrender to God now when we can.

The two lines featured in this chant are drawn from a group of writings attributed to Kabir which are sometimes called his Bhakti poems. The American poet and translator, Robert Bly, who is responsible for introducing a number of non-western ecstatic poets to western audiences, published the Kabir Book in 1977, from where these versions of Kabir are drawn.

In a men’s singing and chanting group with Robert, David Ballman and I experimented with how best to fuse the ecstatic poetry of the Sufis and Bhakti-yogis with music and chanting. Bly used to say that the images in poems enter the body not just through the ears, but in other more mysterious ways as well. I have come to believe that when people are chanting in a powerful sacred language like Sanskrit, something opens inside of them and they become more receptive to subtle poetic images.

The couplet featured in this song bespeaks of the garden of lovers and the divine sweetness that comes from seeking, finding, and embracing God there. The lines also suggests yogic influences on Kabir, for the allusion to the heart’s honey (amrit or nectar) points toward the mystical, tantric center in the chest, the Anahat Chakra.

The couplet featured in this song bespeaks of the garden of lovers and the divine sweetness that comes from seeking, finding, and embracing God there. The lines also suggests yogic influences on Kabir, for the allusion to the heart’s honey (amrit or nectar) points toward the mystical, tantric center in the chest, the Anahat Chakra.

When the heart opens, nectar flows. Was Kabir singing about the heart center? That is for you to decide.

Come, Come, Come, Whoever You Are /La Illaha

Lyric:

Lyric:

Come, come, come

Whoever you are

Wanderer, worshipper,

Lover of leaving

It does not matter.

Ours is not a caravan of despair.

Even if you’ve broken your vows

a thousand times.

Come, come, come, yet again, come.

-Rumi

Sufi Chant:

La Illaha Il Allahu

Translation:

There is only God

Comment:

The opening English lyric is based on a poem by Jelaluddin Rumi, the 13th century Persian poet and Sufi mystic who lived in south central Turkey. He is widely recognized as the greatest of the era’s poets. His Mathnawi, a vast collection of stories and poetry is considered a masterpiece of world literature, and his Mevlana Sufi Order, otherwise known as the Whirling Dervishes, are equally reknown and admired. This translation is by Coleman Barks – a friend of Robert Bly – whose lively versions of Rumi’s poetry has opened, in an unparalleled way, the wonders of this great mystic’s writings to western audiences. Rumi loved music and sacred dance and believed that performing these arts helped center the soul in the Divine essence.

I find these lines moving because Rumi – across some six hundred years – speaks with great compassion about the eternal predicament of spiritual seekers. The spiritual ideal is seen like a sun shining before the soul. Yet we struggle with the self and its manifestations which throw up clouds to block the sun’s light. We make heartfelt vows and then fall short. The reality of our daily life can drag us down into relentless predicaments and defeatist patterns of behavior.

I find these lines moving because Rumi – across some six hundred years – speaks with great compassion about the eternal predicament of spiritual seekers. The spiritual ideal is seen like a sun shining before the soul. Yet we struggle with the self and its manifestations which throw up clouds to block the sun’s light. We make heartfelt vows and then fall short. The reality of our daily life can drag us down into relentless predicaments and defeatist patterns of behavior.

Rumi’s poem provides an alternative to hopelessness. He declares that regardless of your failings you are welcomed into the reassuring presence of his friends, who run a caravan that is “not of despair.” No matter how messed up one’s life is, no matter how deeply one has failed in achieving one’s ideals, no matter how hopeless,

The Sufi chant or wazifa in Arabic – which follows Rumi’s poem – resoundingly proclaims that God is ever present and the ultimate truth of existence. La Illaha Il Allahu!

The Mirabai-Keshava Suite/ Show Me the Bhakti Path

Lyric:

Don’t go, don’t go, I touch your soles. I’m sold to you.

No one knows where to find the Bhakti Path,

Show me where to go.

Turn me into a heap of incense and sandalwood and

You, oh you, set a torch to it.

When I’m fallen down to gray ashes

Smear me on your

shoulders and your chest.

Mira says, You who lifts the mountains,

I have some light.

Let me mingle it with yours.

Keshava Madhava Govinda Bol

Keshava Madhava Hari Hari Bol

I have some light let me mingle it with yours

Show me where the Bhakti path is, show me where to go

Don’t go, I belong to you

Sanskrit Translation:

Lord of beauty; the long haired one and the verdant spring

Redeemer and Preserver of life, Lord Supreme, Everybody Praise!

Comment:

This four part suite fuses our adaptation of a traditional Indian chant with a poem we set to music by one of the greatest of India’s Bhaktis, Mirabai. This translation is based on a version of a Mirabai poem by Robert Bly.

This four part suite fuses our adaptation of a traditional Indian chant with a poem we set to music by one of the greatest of India’s Bhaktis, Mirabai. This translation is based on a version of a Mirabai poem by Robert Bly.

Mirabai (trans. Sister Mira) lived in 16th century Rajasthan in Northern India where she composed her songs and poems in her indigenous Rajasthani language. Today in India, she remains much loved and admired. Along with Kabir, she is a central figure in the Indian spiritual renewal movement known as Bhakti. As a woman, Mirabai embodied the liberatory character of the movement in that she challenged conventions and rejected class and gender distinctions in favor of a vision of human equality. Her astonishing poems mix deep religiousness with a woman’s love poems to God. She pines for communion with the Divine in the form of her Beloved Krishna.

On the Bhakti path, there are periods when the Beloved is present and the heart overflows with love. Other times, the Beloved is gone, leaving feelings of abandonment. In many of the autobiographies of the great Bhakti yogis, episodes such as these are recounted. Mira sings of such a time in this poem. We can see how willing she is to forego her life for her Beloved. Dreams of being turned into a precious  fragrance, burned, and then rubbed onto the shoulders and arms of her love will absolve her of the painful separation.

fragrance, burned, and then rubbed onto the shoulders and arms of her love will absolve her of the painful separation.

The traditional chant sung here is directed to Krishna, a major deity and highly regarded avatar adored by Mira. Another name for Krishna is Keshava, the long haired one, who represents the verdant spring and lush growth of life. Madhava is the one who destroyed the evil demon, and Govinda is the one who redeems the wayward soul by fulfilling the scriptures. Hari is the beloved Lord Supreme. Bol calls out for everybody to join in and sing!

Ya Devi

Lyric:

Ya Devi sarvabooteshu (shraddha, shakti, daya), roopena samstitha

Namastasye Namastasye Namastasye Namo Namaha

Translation:

We salute the Universal Great Mother, who appears (as faith, power, compassion)

Salutations, salutations, salutations to Her.

Comment:

This is an excerpt from a traditional hymn to the Great Mother found in the Devi Mahatmaya, a sacred text dedicated to her stories, teachings, and ceremonies. It offers loving salutations to three of her Divine qualities. The excerpt appears in a larger story of the Great Mother, as recounted here:

This is an excerpt from a traditional hymn to the Great Mother found in the Devi Mahatmaya, a sacred text dedicated to her stories, teachings, and ceremonies. It offers loving salutations to three of her Divine qualities. The excerpt appears in a larger story of the Great Mother, as recounted here:

Long ago, the world was overrun with evil demons.

Groups of marauding devils

destroyed all hope, beauty and human dignity.

It was the darkest of times.

The few remaining noble souls

climbed up to the top of the highest mountain,

and let out a great plea: a prayer for Divine intervention by the Great Mother.

Eventually, the sages’ prayers were heard, and the Goddess manifested as Durga – the Motherpower in the form of vanquisher of evil arrived.

She appeared in the skies, as if issued from the celestial realms,

She appeared in the skies, as if issued from the celestial realms,

went straight at the army of demons

and proceeded to destroy them.

Soon the demons figured out that this was no normal celestial being!

This was Goddess Durga herself! It was their lucky day.

They could end their suffering in demon purgatory if they were killed by one of Durga’s holy weapons.

What a deal! They thought. We’ll take it!

The demons threw themselves on her and she vanquished them quickly and with deadly accuracy.

Each was sent to a heaven realm to live out his days.

Durga saved the world. All the remaining people of good will gave thanks. In India, twice yearly, nine days are set aside to honor Durga during a ceremony called Navatri. This chant is sung at that time. Every morning and every evening, the temple ritual of aarati is performed. Bells are rung as a way of alerting the Divine that worshippers are present. Awake Oh Goddess! We are giving you our unbridled attention! Lights, pleasing sounds, hymns, flowers, mantras and prayers are given in your honor.

Is it any wonder that many believe one of India’s gifts to world culture are these remarkable embodiments of the Divine Feminine?

Durga Ma Ambika

Lyric

Durga Ma Ambika, Hare Durga Ma Ambe

Translation:

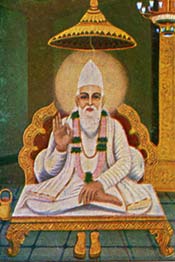

Mataji (Ma Yogashakti)

Praise to Beloved Durga,

The all powerful, invincible yet compassionate

Mother of the Universe

Here is my teacher Mataji (Ma Yogashakti) describing Durga:

“Who is Durga? She is the Divine Power.

God is God only because of His power of manifestation

which is called Shakti or the Primordial Energy.

God is static and immobile in the absence of Shakti.

Shakti is activated energy. Durga is Cosmic Energy.

In truth, energy is the cause of Creation.

Since all beings are directly born

through the womb of a mother,

this Divine Energy, which has caused the birth of creation is called

Mother Shakti-Devi-Prakriti-Durga. (Oh Mother Power, Goddess of Nature & Primordial Energy)

Pray to her in all solemnity with devotion.”

Throughout India, temples stand in honor of Indians’ love for their beloved goddesses. From the tiny whitewashed field temples but three feet high which stand in the corner of fields; to the little statues of a local fertility goddesses, clothed in a colorful little saris and smeared with ochre and sandalwood paste then bathed in water and flowers; to the giant urban Goddess temples which rival any other deity’s in grandeur. She is worshipped as everywhere existing, both transcendent power and uplifting the world through strength and compassion. She is the immanent expression of nature. All of matter, all of life is made of energy from God, and that manifest energy is Durga-Shakti.

The Motherpower Durga Shakti is a rare combination of motherly love and fierce protectoress, a fusion of power and grace, of strength and compassion. We can anticipate that after Durga comes, the world will be a more just, abundant and harmonious place. Praise to Durga!

Hara Hara Mahadevo Shambo

Lyric:

Hara Hara Mahadevo Shambo

Kashi Vishvanath Gange

Kashi Vishvanath Gange

Kashi Amarnath Gange

Love, between the city of the Lord

And the Great Mother River rolling (running) by its door.

Past the Temple of Lord Shiva

Beautiful river, river wide.

Past the Temple of Lord Shiva

Beautiful river, Ganga Mai!

Translation:

Oh Great One, Destroyer

of ignorance and suffering,

Eternally full of happiness

Your abode is the shining city of effulgent light

Oh Great God of Happiness, the celestial river Gang

flows by your city

Comment:

This is an adaptation of a traditional bhajan/kirtan I learned in India, with a second verse added in English, a version of the Sanskrit verse. There is a story here worth telling about how I learned it.

In the winter-spring of 1974 while I was in India, I visited the Haridwar Khumba Mela. The Kumbha Mela is one of the largest religious festivals in the world. It is held every three years in one of four holy sites in India. Haridwar, one of these sites, is an historically religious river town on the banks of the Ganges, at the “doorway” where the mountain river leaves its Himalayan home and tumbles down into the Gangetic plain. Thus the name of this city, Hari-dwar – the door of God. You can stand on the bluffs of the city with the Himalayas looming behind, and see the Ganges winding off to the west and south, coursing through Northern India on its long journey to the Bay of Bengal.

Haridwar is famous for a ghat – a sacred bathing site – where a revered temple to the Hindu Diety Vishnu stands. The temple features a large rock with an imprint that looks like a foot, thus devotees call the place, Har ki Pauri: God’s footprint. Ghats lie all along the Ganges. They mark where devout Hindus go to seek ablution for their sins by bathing in its holy waters. This ghat has a footprint of a God on it!

Every twelve years, during the Kumbha Mela, the population of Haridwar swells a thousand fold. Pilgrims, devotees, Sannyasis (Hindu monks and nuns), yogis and tourists from every walk of life converge on Haridwar for periods of worship, to receive darshan from saints, to listen to sermons from religious leaders, to visit holy sites, and to bathe in Mother Ganges. The visitors, estimated at two million for the 1974 Haridwar Kumbha Mela, crowd into camps located in a vast field of tents on the river plain below. Soon the city begins to mirror the river, as the streets of Haridwar, teeming with pilgrims become streams of humanity. Simply stepping out onto the street is to be carried along in that river.

That was the situation in Haridwar when I arrived in the Spring of 1974. It was unlike anything I had ever experienced before. Extraordinary experiences began immediately. Shortly after I arrived, I was taken by a sannyasi (Hindu monk) of the large ashram I was staying in, to a gate with a two story fence around it. We stood on the ramparts and looked out onto the streets below. Lines of yogis coming down from their mountain retreats in the Himalayas were wandering onto the streets of Haridwar.

At the Haridwar Kumbha Mela, my teacher, Mataji was honored with a saintly title, Maha Mandaleshwar, which translates as “Great Circle of God.” It is an honorific in recognition of her many accomplishments. She was one of the first Indian women to receive this high distinction. I was fortunate to be part of Mataji’s entourage in Haridwar. One day we were alerted about the honor to be bestowed on Mataji and went to observe.

At the Haridwar Kumbha Mela, my teacher, Mataji was honored with a saintly title, Maha Mandaleshwar, which translates as “Great Circle of God.” It is an honorific in recognition of her many accomplishments. She was one of the first Indian women to receive this high distinction. I was fortunate to be part of Mataji’s entourage in Haridwar. One day we were alerted about the honor to be bestowed on Mataji and went to observe.

The meeting room where the announcement was made was an open air verandah, part of a larger ashram-temple complex run by the Niranjani Akhada, a religious organization. The Ganges rolled along not far away. Seated in the room was about a dozen heavily bearded, long-haired turbaned or shaven headed monks, dressed in the customary ochre robes. This was the head council of the Niranjani Akhada. Spread on the floor were Oriental rugs and cushions. From an altar adorned with religious objects in the middle of the room, smoke wafted from sticks of incense. The atmosphere was solemn and honorific. There, in the middle of this council of large sage-like-looking men, sat the only woman, tiny Mataji (who is under five feet tall). She had a half a dozen flower lais on, and was holding her own with a radiantly hypnotic gaze. These venerable gurus and monastery abbots were all paying tribute to Mataji.

A couple of days later, it was time for one of the many holy processions during the Kumbha Mela. This one was sponsored by the Niranjani Akhada. The parade began at the ashram and marched to the Har ki Pauri Ghat for special ceremonies. The route crossed the Ganges, snaked up the other side of the river, and then crossed the river again at the bridge to Har ki Pauri, where the dignitaries of the Akhada would perform a ritual bath in the river. The timing of the entire affair was set by priests who, according to Hindu cosmology, determined the most auspicious hour for the ritual ablution.

I marched in the procession carrying a flag on a long bamboo pole. Mataji – one of the honored guests – was carried on a palanquin by a group of sannyasis. Along the length of the parade, sauntered heavily decorated and bepainted elephants and horses, and there were musicians banging drums, blowing trumpet-like horns, and clanging cartals (brass cymbals). Dozens upon dozens of sannyasis in their ochre robes marched along. Even more visually arresting were hundreds of dreadlocked, bearded yogis called “Naths” who signaled their ritual death to the material world by wearing nothing but white cremation ash smeared on their bodies. They lent an otherworldly sight to the affair.

I marched in the procession carrying a flag on a long bamboo pole. Mataji – one of the honored guests – was carried on a palanquin by a group of sannyasis. Along the length of the parade, sauntered heavily decorated and bepainted elephants and horses, and there were musicians banging drums, blowing trumpet-like horns, and clanging cartals (brass cymbals). Dozens upon dozens of sannyasis in their ochre robes marched along. Even more visually arresting were hundreds of dreadlocked, bearded yogis called “Naths” who signaled their ritual death to the material world by wearing nothing but white cremation ash smeared on their bodies. They lent an otherworldly sight to the affair.

We marched along a promenade before thousands of admiring pilgrims. Up ahead, a mile away, lay the red roofs of the temples of the Har ki Pauri Ghat and several colorful bridges arching across the river. Up beyond that, in the far distance, the Himalayas beckoned. Running through this fantastic scene was the great Mother River, the Ganges.

In the Hindu world view, there are two Ganges: the physical river and the celestial river. They both nourish life and exist simultaneously in two worlds. Heaven is where one spouts. The Himalayas is where the other one comes from. In all actuality, the two are one and the same, but that is another story.

In Hindu mythology, Mother Ganges flows out of Shiva’s hair! For the pilgrims and the devout, whether referring to physical river or celestial river, or whether addressing the human soul or the immanent Divine, both are made of the same holy stuff.

In Hindu mythology, Mother Ganges flows out of Shiva’s hair! For the pilgrims and the devout, whether referring to physical river or celestial river, or whether addressing the human soul or the immanent Divine, both are made of the same holy stuff.

A short time into the procession, I heard a chant rise up among the pilgrims who were strung along the parade route. Suddenly, women – dozens of them – came out of the crowd and joined in the parade to celebrate Mataji’s accomplishment. They began singing the Hara Hara Mahadevo Shambo chant to the Holy River Ganges and to the cities of the Lord which it passes through on its way from the mountains to the sea. It was a spontaneous outpouring of joy and love.

Crossing time’s decades, continents and oceans, I now live along another grand and storied river, the Mississippi. It runs the length of the state of my birth – Minnesota – before sluicing south on its long journey through the heartland to the Gulf of Mexico.

My city – Minneapolis – was founded where the Mississippi, in pre-historic time, cut a gash through a bed of limestone, creating an impressive gorge of rocky, tree lined bluffs. It is a dramatic place of waterfalls, tall oaks and maples. The indigenous people first recognized it as a sacred place. Later, it was admired by European settlers who built a city here. The name Minneapolis is drawn from an old Indian phrase joined to the Greek polis meaning “City of Laughing Waters.”

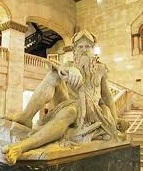

In Minneapolis’s City Hall, in the North Rotunda, there is a fantastic marble sculpture reflecting one artist’s vision of the Mississippi. Fashioned in the form of a water deity, it is entitled, “The Father of Waters.” He is a bearded, powerful looking old patriarch, an ancient Greek sculpture married to indigenous nature, the Water God Neptune and Old Man River combined in one. Half supine, he is surrounded by the river’s aquatic life: fish, turtles, water plants and foliage. I like to think the Hara Hara Mahadevo chant which celebrates the sacred cities of India lying along Mother Ganga’s shores, mirrors, mysteriously, the “Father Mississippi” coursing through the North American heartland.

In Minneapolis’s City Hall, in the North Rotunda, there is a fantastic marble sculpture reflecting one artist’s vision of the Mississippi. Fashioned in the form of a water deity, it is entitled, “The Father of Waters.” He is a bearded, powerful looking old patriarch, an ancient Greek sculpture married to indigenous nature, the Water God Neptune and Old Man River combined in one. Half supine, he is surrounded by the river’s aquatic life: fish, turtles, water plants and foliage. I like to think the Hara Hara Mahadevo chant which celebrates the sacred cities of India lying along Mother Ganga’s shores, mirrors, mysteriously, the “Father Mississippi” coursing through the North American heartland.

Ganges and the Mississippi?

India and America?

East and West?

What are they but two great rivers?

Up and down those shores

Soul- turning melodies and timeless rhythms

are being born.

Listen.

By David Schmit © 2012